When Liverpool and Tottenham Hotspur take to the Wanda Metropolitano pitch for the Champions League, they will of course carry large advertisements for Standard Chartered Bank and the insurance company AIA.

Shirt sponsors are nothing new, of course, but the journey towards such widespread exposure in European competitions has been one with a few twists and turns.

UEFA first allowed teams to promote companies on their chests in 1982. The nettle had been grasped in England in 1979 as Liverpool joined forces with Hitachi – Kettering Town had tested the Football Association two years earlier with their Kettering Tyres sponsorship. Even prior to that, though, there were problems regarding kit manufacturers’ logos for the 1981 European Cup final between Liverpool and Real Madrid.

The undercurrent was part of adidas’s quest to seize the Liverpool contract from Umbro and the boss of the German firm convinced UEFA that makers’ logos shouldn’t be allowed for the Wembley final. To back up the view, he showed them that the Real shirts didn’t have the famous trefoil and so Liverpool should likewise have to cover the double diamond. What went unremarked upon at the time was that Real’s white shirts still had the recognisable three-stripe motif.

By the time the Reds took to a European field with a sponsor’s name, against Dundalk at the start of 1982-83, it was Crown Paints adorning the shirts.

However, while Uefa were willing to allow sponsors for ‘normal’ games, their television agreement with the European Broadcasting Union meant that the finals of the European Cup and the European Cup Winners’ Cup would remain sponsor-free zones.

The first winners of the European Cup after the change in sponsor rules was German side Hamburg. For the final win over Juventus, they reverted to their previous practice of having ‘HSV’ on the front of their shirts.

The practice of allowing sponsors up to, but excluding, the final continued until the early 1990s, when the advent of the Champions League brought another change – having negotiated deals with firms who became partners of the new venture, UEFA prohibited sponsors for the group stages of the competition in 1992-93 and 1993-94.

This posed a slight problem for Rangers ahead of their first group game against Marseille at Ibrox. Adidas had only sent a set of short-sleeved unsponsored shirts and Mark Hately, Trevor Steven and Alexei Mikhailichenko all favoured long sleeves. The quick compromise was that they wore sponsored shirts, as used domestically, but with patches sewn over the McEwan’s Lager logo (see second photo).

PSV Eindhoven decided to take what advantage they could. Owned by electrical giant Philips (the ‘P’ in PSV), they registered themselves as ‘Philips SV’ and added text above their crest, meaning they were effectively the only team to have their sponsor’s name on their kit.

The 1994 final between Milan and Barcelona would prove to be the last between teams in unsponsored shirts, though of course Barça didn’t have one at the time anyway.

However, while the following season would see the rules on sponsors’ logos relaxed, UEFA were in clamp-down mode regarding the ubiquity of manufacturers’ markings and so imposed heavy limits. So it was that the Barcelona kit featured above – a strip produced especially for continental games – was shorn of the Kappa logos on the neck, sleeves and shorts for 1994-95, with the fabric pattern also disappearing.

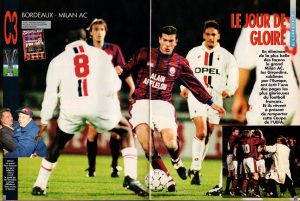

Ajax would go on to become the first club to win the European Cup or Champions League with a sponsor’s logo – though not across their chest, funnily enough – as they dethroned Milan in the final.

You’ll notice that the Milan kit didn’t have the lightning-bolt logo which appeared on their domestic kits – this was due to rules on the area taken up by the sponsors. This would remain in place until 1998-99 – compare how Milan filled the ‘gap’ created whereas another Opel side, Bayern Munich, did not.

UEFA continue to keep a firm grip on the rules regarding sponsors, though nowadays the only noticeable difference between domestic and continental kits is that the latter doesn’t allow sleeve or back sponsors, though there is the facility for a charity promotion instead. Given that the European governing body always have their business heads screwed on, shall we say, it will be interesting to see if any changes are forthcoming in the future.

This blog was written by Museum of Jerseys. Please visit their website to read more interesting articles!